Why it is Important

When people can connect to a concept on an intellectual or emotional level, they are more likely to engage with it, remember it, and learn from it.1 It is our job as exhibit and program designers to facilitate these connections that lead to memory and meaning making. See the Relevant Design Strategy page for more information.

Put it into Practice

One of the most effective ways to make connections between content and the family audience is to tell the story through people.

Telling the Story through People

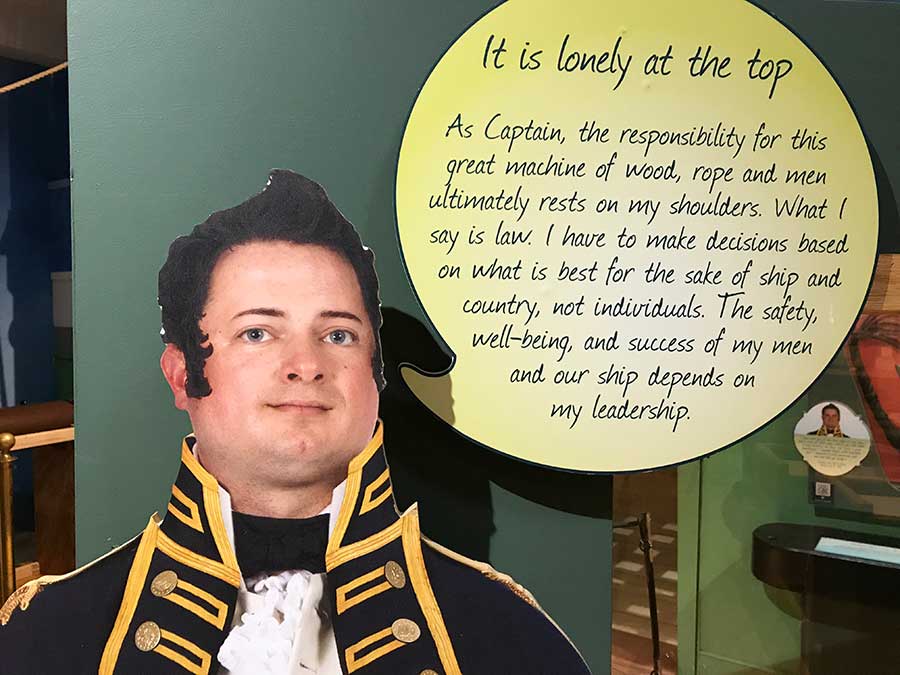

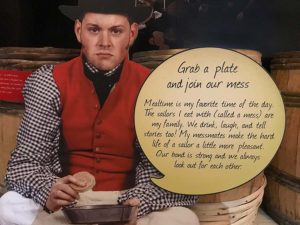

People connect with people. The USS Constitution Museum’s exhibit, All Hands on Deck, interprets Constitution through the experience of her crew. This interpretive strategy resonates with our family audience. By telling the story through people, our visitors can connect on a personal level, enabling families to imagine themselves in the sailors’ shoes and fostering empathy for what the sailors went through. To help bring the crew to life, full-scale photo cutouts visually “people” the exhibit and the text is written as if visitors are hearing sailors’ stories first-hand. We feature a diverse range of crew members and the families they left behind. The inclusive interpretation provides visitors of different ages, genders, and ethnicities the opportunity to “see themselves” in the exhibit.

First-Person Narratives

At the USS Constitution Museum, we conducted audience research focused on how to present history in engaging ways. After testing different types of interpretive labels with visitors, we learned that 64% of families preferred labels written in first-person voice as opposed to a third-person curatorial voice. These visitors reported that they preferred the conversational, first-person voice because it felt like the historical cutout was speaking directly to them. When asked about the first-person approach, one visitor commented:

“When I come to a history museum I want my family to hear it from the people who lived it, not a secondary dry account. History should be alive and this type of label gives you a chance to be a part of that.”

As a result of this research, we wrote a large number of panels in first-person. Here is an example from our exhibit panel in the mess area of All Hands on Deck:

“Grab a Plate and Join Our Mess. Mealtime is my favorite time of the day. The sailors I eat with (called a mess) are my family. We drink, laugh and tell stories too! My messmates make the hard life of a sailor a little more pleasant. Our bond is strong and we always look out for each other.”

Connect to the Human Experience

Instead of describing battle tactics and a slavish blow-by-blow of how battle transpired over several hours, the USS Constitution Museum focused on broad human experience and concepts, such as anticipation and fear. This approach captured our visitors’ interest and enabled us to make connections to their own lives. We asked a series of questions to make the sailors’ experiences in 1812 relevant to lives today. Our panel on “anticipation” is one example:

“…My pulse beat quick – all nature seemed wrapped in awful suspense – the dart of death hung as if it were trembling by a single hair, and no one knew on whose head it would fall.”

—David C. Bunnell

In preparing for battle, the crew executes a set of well-orchestrated tasks and then waits at their guns. Hours pass from the first sighting of the enemy sail until the engagement begins. The crew experiences a range of emotions while they stand in silence at their battle stations anticipating the ultimate test.

What do sailors feel as they wait for battle to begin?

- Fear – Sailors worry that they or their friends might not survive the battle. What frightens you?

- Excitement –The adrenaline pumps as the moment the sailors have been training for arrives. How do you feel when something you’ve waited for is about to happen?

- Anxiety – Sailors are nervous because no one knows the outcome of the battle. What makes you anxious?

Ask Questions that Bring Families into the Story

Questions can be an effective tool to promote conversations and to personalize the information so families can make a personal connection. The simplest and most popular text panel in the USS Constitution Museum is “How do you compare to an average sailor?”

Visitors can measure their own height on a measuring tape next to the graphic silhouette of a sailor that reads:

- How tall are you?

The average height was 5’ 6 1/2”. - How old are you?

The average age was 27 but some were under 15 or over 50. - What color are your eyes?

The most typical eye color was gray. - What color is your hair?

The majority of sailors had brown hair tied back in a short pigtail. - What color is your skin?

7%-15% were free black men; etc.

This personal delivery method of otherwise mundane material brings the visitor right into the story and conveys the message that sailors nearly 200 years ago were a lot like us.